Applied Nutrition And Feeding Management Of Sows

Introduction

In the recent past, nutrient requirements and feeding management of gestating and lactating gilts

and sows have changed dramatically along with genetic improvements although fundamentally, the

list of nutrients required by the sows and how they are used have remained much the same. While

it has been a common practice to select replacement animals from marketable pigs, gilts now are

routinely purchased from breed-specific multiplier herds genetically improved for prolific reproduction

and lean meat composition. It is now realized that reproductive performance, as measured by pigs

produced per sow per year, has a major effect on profitability for the swine producer. As productivity

is greater in sows than gilts, management of the breeding herd must be focused on maintaining sows

in the herd as long as possible.

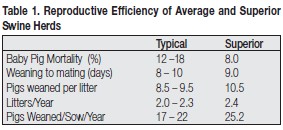

Adequate nutrition of the breeding herd is necessary to maximize herd productivity and overall profitability. If comparison is made between the reproductive efficiency of herds obtaining average productivity with those obtaining higher levels of performance, it is evident that there is considerable room for improvement (Table 1). However, maximum reproductive efficiency can never be obtained unless the best feeding and management practices are also followed. Unfortunately, many producers try to reduce cost by cutting back on the quality of the diet. It is well documented that feeding poor quality diets will affect reproductive performance. Failure to meet the nutrient needs of the sow may result in smaller litters, a reduction in piglet weight and vigor, lower milk production, an increase in the weaning to service interval, a reduction in conception rates and a shorter reproductive lifespan. Attention should be given to the quantity and quality of feed in terms of energy, fiber, amino acids and protein fed daily through the various stages of growth, pregnancy and lactation. Individual animals or groups of animals with similar performance and body composition need to be considered. Achieving a normal parity distribution in the herd with five or six parity sows being replaced by new gilts will assist greatly in feeding management and overall profitability. This paper discusses some nutritional and feeding management strategies for maximizing performance and profitability of the breeding herd.

The feeding program of the breeding herd should be based on genotype, sow longevity, the type of housing employed, and the nature of the current sow herd in terms of appetite and body condition.

Feeding And Management Of The Replacement Gilts

Selection of replacement gilts should be done as early as the growing stage (50-60 kg ABW) at a

culling rate of between 30-50%. This, plus proper feeding management will improve the replacement

gilt productivity which will significantly impact reproductive performance of the entire herd. Gilt

productivity is influenced by the following factors, i.e., age at successful mating, first parity litter size,

and the ability to be successfully bred.

Nutrition during the rearing period (20-100 kg), through its effect on body weight and backfat levels can influence the age at which puberty is attained. Restricting the intake of young growing gilts (50- 85% of ad libitum intake) will delay onset of puberty by 10-14 days. Feed at least 8360 kcal/day between selection and mating. Severe protein restriction or amino acids imbalance will significantly delay onset of puberty. Diet should contain 15% CP (466 g/day) and 0.7% lysine (217 g/day). The diet should also contain higher calcium and phosphorous to maximize bone mineralization as this has been shown to improve reproductive longevity. The minimum level required for calcium is 0.8% (25.4 g/day) and 0.73% for phosphorous (22.6 g/day).

The aim in feeding the gilt is to have her reach 120 kg at 210 days, be ready for mating at second or third estrus and have a P2 body fat measurement of 18-20 mm (Partridge, 2000). Gilts that are too thin may experience poor fertility and delayed estrus after weaning. Excessive fatness in gilts will also lead to poor reproduction and difficulties in parturition. P2 fat thickness greater than 25 mm should be avoided. Flushing, or feeding higher nutrient levels, is recommended for a 10-14 day period before the expected date of breeding as this increases ovulation rate especially in first litter gilts. Feeding of broad-spectrum antibiotics just prior to mating has also been shown to increase litter size born in at least four experiments (Easter, 1994). There is no evidence that continued antibiotic feeding during gestation offers any significant benefit.

Feeding Gilts Prior To Breeding

Ovulation rate is the principal factor limiting litter size in gilts. Increasing the level of feed during the

rearing period will significantly increase ovulation rate at puberty. Short-term, high level feeding (flushing)

during the first estrus increases ovulation rate compared with gilts fed restricted amounts of feed.

Ovulation rate increases by about two (2) ova in response to increased feed intake during the 14-

day period prior to ovulation. Flushing has been shown to increase plasma levels of FSH and increase

the pulse frequency of LH suggesting that it enhances ovulation rate by stimulating secretion of

gonadotrophins. It has been thought that the increase in gonadotrophin secretion is mediated through

plasma levels of insulin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1).

Feeding Gilts Following Mating

Approximately 30% of all potentially viable embryos die during the first 25 days of gestation. Increasing

the level of during the first 72 hours from 1.8 kg to 2.5 kg/day after mating increases embryonic

mortality. This was associated with a 10-hour delay in the normal rise in plasma progesterone (this

hormone enhances the uterine environment to support the embryo).

Feeding The Sow During Gestation

The key to successful sow feeding is built around the principle of generous feeding during lactation

and strict rationing during gestation. Feed consumption during the gestation stage should be between

1.8 to 2.7 kg for gilts and sows. Increasing feed intake will dramatically increase weight gain but has

little or no effect on weight of new born piglets. Each sow is an individual and thus will react differently

to nutrient intake. It is thus best to feed sows individually and daily ration should be based on body

condition, ABW, method of housing, the environment provided, herd health, productivity level and

standard of management.

Thin sows have less thermal insulation than fat sows and will be less able to adjust to lower environmental temperature and would require an increase in feed intake under this condition. Heavier sows have higher maintenance requirement i.e., energy requirement increases by about 5% for every 10 kg increase in ABW. Sows housed at lower temperatures require more feed. For individually house sows, the lower critical temperature is about 16-18°C. Below this level, intake should be increased by 3-4% for every 1° lower.

Health of the herd affects the feeding level required during gestation. Sows infected with worms may actually lose weight through gestation and will have small litters.

Various management systems are used to limit feed intake during gestation which include the following; hand feeding using gestation stalls, computer-controlled feeding stations, slow feeding systems, selfclosing individual stalls, skip-a-day feeding and self-feeding high fiber rations.

Sows will greatly over consume energy if allowed to consume a nutrient dense diet ad libitum. Over fat sows will have difficulty in farrowing, have an increased incidence of stillborn births, a higher tendency to crush piglets, will have reduced feed intake during lactation and will be difficult to rebreed after weaning. Over feeding in gestation impairs metabolism and results in feed intake depression during lactation. High concentration of free fatty acids and low concentrations of branched chain amino acids in blood plasma are observed and may depress feed intake by acting on the appetite centers in the brain. This effect is amplified during periods of high environmental temperature and humidity

Feeding Fiber During Gestation

Gestating sows are well suited to consume high fiber diets. Sows can obtain some energy from

dietary fiber using hindgut fermentation. Low energy and high fiber diets reduce constipation problems

and are useful to prevent obesity in sows. The larger gut fill with low energy and high fiber gestation

feed enhances feed intake when the sows are transferred to their higher energy lactation diets.

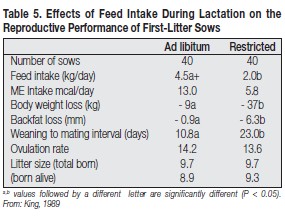

In a 25-study review conducted by Reece (1997) on feeding of fiber to gestating sows, it was concluded that dietary fiber increases number of pigs born alive, number of pigs weaned and average weaning weight. Results are presented in Table 3. In addition, increased dietary fiber during gestation reduced stress behavior in sows such as licking, bar biting and sham chewing.

Nutrients Required During Gestation

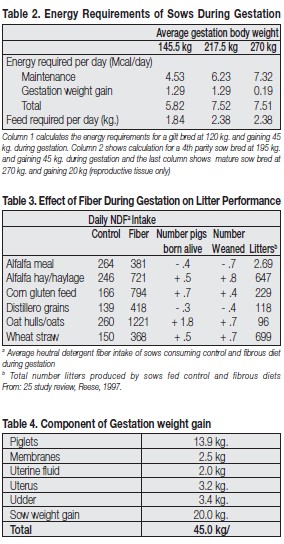

Energy

High quality diet is necessary to provide adequate

levels of nutrients for fetal, uterine, mammary and

body growth and replenishment of body reserves

depleted during the previous lactation. The

maintenance requirement is 110 kcal DE/kg 75

per day and represents in excess of 75% of sow’s

daily energy requirement. The energy requirement

for maternal growth is set by the desired body

weight during gestation Table 2 shows the energy

requirement of sows at different body weights.

The gilt or sow should gain weight during

pregnancy to compensate for the weight of the

litter and fetal membranes and to allow for normal

increase in body weight. The rule of thumb is to

target for 20-25 kg of maternal weight gain (3

to 4 parities) and 20 kg of reproductive tissues

per parity at least up until the fifth parity when

mature size is achieved (Table 3). The greater the

energy intake and weight gain in pregnancy, the

greater the weight loss in lactation. An increase

in the NE intake of pregnant sows above 6 kcal

per day will increase maternal weight gain but

will not significantly affect litter size at birth.

Protein And Amino Acids

Amino acids are needed during pregnancy to

replace those lost through obligatory sloughing

or metabolism. During gestation, there is

continuous sloughing of cells from tissues such

as skin and intestinal mucosa which represents

obligatory losses of amino acids from the body

and which should be replaced to maintain

condition. This represents the maintenance requirement. Amino acids are also required for the development of the mammary glands and to add

protein to the maternal body. Reproductive characteristics such as litter size, birth weight, breeding

regularity and fertility show little response to protein intakes greater than about 140 grams per day.

However, to maintain sow body condition for subsequent reproduction, 180 grams per day of crude

protein is recommended for sows weighing 140 kg and gaining 20-25 kg in maternal live weight

during pregnancy (King, 1990). This assumes that the protein has the correct balance of essential

amino acids (NRC, 1998) and provides at least 7 grams of available lysine per day.

Vitamins

Vitamins has been recognized to have an essential role in reproduction. There had been evidences

that current recommendations are inadequate for several vitamins specifically folic acid, beta-carotene

and Vitamin E. Folic acid has been found to increase litter size attributed to reduction in embryonic

mortality (the rate of cell proliferation during embryonic development is extremely high and the

intracellular concentration of RNA, a key component is highly correlated with embryonic survival. Its

synthesis, along with DNA requires purines and pyrimidine bases, the production of which requires

single carbon units and folic acid is an indispensable cofactor in the metabolic transfer of single

carbon units). Beta-carotene, a natural precursor of Vitamin A but recent evidences suggest that it

may have a unique role in reproduction independent of its function as a precursor of Vitamin A. This

is manifested in increased litter size (beta-carotene can increase the production of uterine specific proteins which support embryo survival. A basic glyco protein with iron binding capacity and a group

of acidic proteins with immunosuppressive capabilities had been identified which play key roles in

embryo development. Beta-carotene may also increase the production of progesterone during the

initial formation of the corpus lutea). Vitamin E can increase litter size at birth and weaning at higher

levels than recommended.

Feeding The Sow Around Farrowing Time

Excessive restriction prior to and for the first few days after farrowing can cause excessive sow

excitement due to hunger resulting in an increase in piglet deaths due to crushing. It is best to maintain

the same level of feed intake as that normally fed during gestation (2 – 2.5 kg). Following farrowing,

a gradual increase in feed intake is recommended, with the objective of getting the sow to maximize

feed intake as soon as possible into lactation.

Feeding The Sow During Lactation

The long term reproductive efficiency of the sow is best served by minimizing weight loss during lactation

(Dourmad et al., 1994). The daily energy requirements during lactation include a requirement for

maintenance and a requirement for milk production. The objective of feeding during lactation is to allow

the sow to produce enough quality milk for her piglets and prevent excessive weight loss so that estrus

and rebreeding can occur soon after weaning. Most sows should be fed ad libitum during lactation after

a build-up of feed intake over the first few days. Voluntary feed intake, however, may still fall below the

estimates of energy required causing weight loss. Appetite can be encouraged by keeping sows cool

and well ventilated and by feeding wet feed or liquid feed in specialized feeders. Sprinklers and snout

drips are useful in keeping sows cool. Dietary fat and inclusion of full-fat soybean meal will also improve

palatability and feed energy intake.

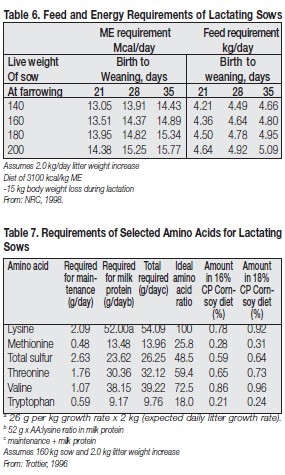

Milk output is slow at the start of lactation and reaches a peak about three weeks after farrowing. Requirements during lactation depend on the number of piglets consuming milk. Sows satisfy requirements for amino acids and energy during lactation first from dietary intake, and then from body reserves. Weight loss during lactation must be controlled. Even in short lactations, it is almost impossible to prevent some fat loss. Table 5 shows the effects of feed and energy intake during lactation on the reproductive performance of first-litter sows. Table 5 gives estimates of the feed requirements according to the sow and length of lactation. These assume a litter of 10 pigs growing at an average of 2.0 kg per day for the litter.

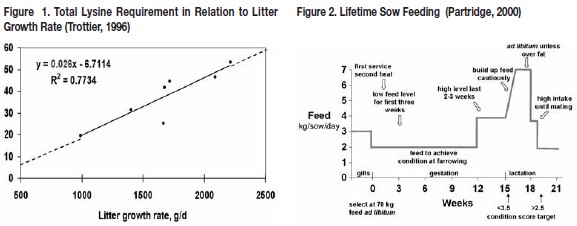

Consideration of requirements for protein and amino acids are extremely important in lactating sows. Lactating sows require amino acids for milk production and maintenance. As much as onethird of sow weight loss during lactation may be lean tissue. Muscle protein is degraded to supply amino acids for milk production. The amino acid requirements depend on the level of milk production. Once feed intake is established according to energy requirements, the diet can be balanced for protein and amino acids using the values in Table 7 (2 kg expected daily litter growth). The data in Figure 1 can be used for litters growing more or less than 2.0 kg per day. In this case, the ratio of amino acids to lysine will be slightly different than what is given in Table 6 as the ratio of amino acids required for maintenance and milk production is different. Feeding in one part of the breeding cycle should not be considered alone. What happens during pregnancy will for example affect later performance. Poor lactation feeding can affect rebreeding and sows that have lost much weight in lactation attempt to restore this by making rapid weight gains in the next gestation cycle. This can induce a hormone imbalance leading to death of embryos and reduced litter size (Partridge, 2000). Figure 2 shows an ideal scheme of sow feeding throughout the reproductive life.

Sow Longevity And Parity Distribution

Litter size and piglet weights increase until the fourth and fifth parities, and the number of pigs weaned

per sow per year increases until the sixth and seventh parities. As the number of pigs weaned per

sow per year is directly related to the profitability of the operation, it is important to consider sow

longevity and what can be done to increase it. Ideally, the average parity in the breeding herd should

be four or five with and be evenly distributed. Abnormal distribution of sows across parities may

indicate poor feeding management. The most typical reasons for removing young sows from the herd are anestrus and repeat breeding. Extension of the weaning to mating interval is a particular problem

in first-litter sows. Approximately 50% of these animals may fail to exhibit estrus within one week of

weaning. Failure to reproduce efficiently accounts for up to 39% of reasons for culling of early parity

sows. Of these, 20% are culled after first parity. A major reason for reproductive problems is inadequate

feed intake during lactation. This causes excessive tissue loss and extends the weaning to estrus

interval and results in overall low conception rates.

Feeding Fat During Lactation

Evidence suggests that fat addition to the diets of sows during late gestation and lactation increases

milk yield, fat content of colostrum and milk, and survival of pigs from birth to weaning (Pettigrew and

Moser, 1991). Fat supplementation reduces weight loss during lactation and decreases the interval

from weaning to mating. Fat can be supplied in the form of liquid fat added to the dry feed ingredients

or as dry fat or in the form of full fat soybean meal. Consideration should be given to fat quality in

terms of fatty acid composition. Fat sources such as soy oil that contain high levels of essential linoleic

acid are excellent choices. Oxidation should be prevented as rancid fats are not palatable and have

a negative effect on feed quality and animal metabolism. Of interest is the possibility that sows may

be able to utilize raw soybeans. A study conducted by Crenshaw and Danielson (1985) suggested

no reduction in breeding performance from feeds containing 10% and 15% raw full fat soy in gestation

and lactation diets respectively.

Conclusion And Recommendations

Sows should be fed depending on their stage of production. Energy and nutrients should be maximized

before mating (flushing) maintaining a feed intake of about 2.5-3.0 kg until the sow is bred, restricted

during gestation and supplied ad libitum during lactation. During pregnancy, the sow can cope with

marginal nutrient deficiencies. Modern sows have more defined nutrient requirements than sows 20

years ago. Average weaning age is decreasing and sows have higher farrowing rates. Weight loss

of sows nursing large litters and heavier piglets should be minimized as much as possible. Environmental

factors such as temperature, humidity and house design affect feed intake and should be considered.

Gestating sows should be fed so they do not become too fat or too thin. First litter gilts should not

be culled if the feeding program does not allow them to return to estrus quickly. The energy and

protein requirements of lactating sows should be based on the litter size and expected growth rate

of the litter. For each one kilogram per day of litter growth, the lactating sow should consume 26

grams of available lysine (in proper balance with other amino acids) and 10,000 kcal of metabolizable

energy per day. Nutrients should be considered on a daily amount basis instead of as a percent of

diet. The litter growth rate and sow feed intake should be measured in order to establish feed and

nutrient intake levels. Records of feed intake, average parity, parity distribution and culling rates should

be kept. Fat sources such as liquid and dry fat and full fat soy are excellent sources of energy and

should be used during lactation and flushing.

Nutri Animalé, Inc.

Philippines

Tags · Applied Nutrition And Feeding Management Of Sows

This article hasn't been commented yet.

Write a comment

* = required field